Supporting lung cancer screening in the community

GP respiratory specialist Dr Daryl Freeman FRCGP provides an update on the UK’s Targeted Lung Cancer Screening Programme and explains how nurses in the community can play a crucial role in supporting lung cancer screening and early detection

The need for early detection in lung cancer

There has been an urgent and growing need to improve early detection of lung cancer. Lung cancer remains the UK’s biggest cancer killer.1 It is responsible for 21% of all cancer deaths, with 34,771 people dying of the disease each year.1 It is the third most common cancer, accounting for 13% of all new cancer cases.1

Currently, around one-third (32%) of lung cancers are diagnosed via emergency admission to hospital,2 and the five-year relative survival compares poorly with other European countries.1,3

Numerous studies have shown lung cancer screening is the best prevention method for reducing lung cancer mortality.4-6 If detected early (at stage I) 65 people out of 100 will survive lung cancer – compared to just five if diagnosed late (at stage IV).7 Diagnosing people earlier means they are generally fitter and therefore can receive treatment with curative intent.

What are the risk factors for lung cancer?

Most (72%) lung cancer cases are caused by smoking, according to latest data.1 The UK Lung Cancer Coalition (UKLCC) and its members and stakeholders have steadfastly campaigned for a Smokefree Britain. Other risk factors include workplace exposures, ionising radiation and air pollution. Older age is a significant risk factor, reflecting DNA damage accumulation over time, and genetic factors may also play a role.1 Indeed, lung cancer in never smokers is now the eighth most common cause of cancer-related death in the UK.18

Lung cancer is strongly linked to socioeconomic status. The incidence of lung cancer is 168% higher for men living in the most deprived areas of the UK compared with those in the least deprived, and 174% higher for women in the most versus least deprived areas.1 Patients with lung cancer living in more socioeconomically deprived circumstances are less likely to receive any type of treatment, surgery, and chemotherapy.9 It is therefore no surprise that while a quarter (25.3%) of people in England diagnosed with lung cancer in the least deprived group survive their disease for five years or more, less than a fifth (18.2%) do in the most deprived.1

Related Article: Mythbuster: ‘I don’t need a smear test – I’ve had my HPV jab’

What does the national screening programme involve?

It has now been over a year since the Government finally approved a national targeted screening programme, in June 2023. This followed the positive recommendation made by the UK National Screening Committee, and the success of NHS England’s Targeted Lung Health Check (TLHC) pilot scheme.10,11 As a result, not only will many lives be saved, but it will also provide a major opportunity to address the health inequalities linked to lung cancer.

Patients with a smoking history aged 55-74 are now being invited for screening. Individuals are identified from GP records and invited to a lung health check by letter, email or text message, sent by the GP practice or Integrated Care Board (depending on local arrangements). The health check will then be conducted in person, by phone, or online, with individuals questioned about their breathing, lifestyle, and family and medical history. Height and weight measurements are also recorded.

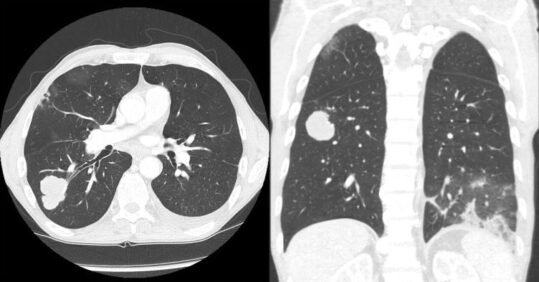

Any concerns with a patient’s lung health are referred to their GP and current smokers will be offered advice on how to stop smoking. Individuals considered high risk of developing lung cancer (assessed on factors such as: number of smoking years; age; previous malignancies; family history of lung cancer; comorbidities such as COPD and any history of pneumonia; and contact with asbestos) will be immediately referred for a low-dose CT scan and thereafter recalled for repeated scans every two years.

Any patient whose CT shows suspicion of lung cancer will be triaged by the radiology or respiratory clinic for biopsy and other further tests. The National Optimal Lung Cancer Pathway details how patients will be followed up depending on results.

Note that some people may require investigation and follow up of abnormalities that turn out to be benign, including monitoring of pulmonary nodules, which can potentially cause anxiety for these individuals. However, the National Screening Committee evaluation found that overall the benefits of early identification of cancer outweigh any risks in this population.

What has been achieved to date?

Currently, there are 43 active TLHC sites in England. Since April 2019 more than 1.5 million people have been invited for a check and over 3,600 lung cancers in total have been diagnosed – three quarters of them early (stage I or II). Previously, without screening, the rate of early-stage diagnosis was 28.9%.12,13

The TLHC projects were initially rolled out in areas of high deprivation. The latest Rapid Cancer Registration Dataset now shows that people from disadvantaged areas are now most likely to be diagnosed with lung cancer early. In addition, the screening has also led to other cancers being detected.13,14

National Lung Cancer Audit data also recently revealed that the proportion of lung cancer patients diagnosed with stage I/II disease has increased from 30.5% in 2021 to 33.8% in England – and from 24% in 2021 to 30% in Wales. Some of the increase in England can likely be attributed to the impact of the TLHC Programme.2

Are there any other national lung cancer screening programmes in the UK?

The UK Screening Committee advocated a UK-wide targeted screening programme – yet, to date, the roll out is only being implemented in England. There are no equivalent initiatives in Scotland and Northern Ireland, although a pilot lung health check is underway in Wales, which has now screened 500 people.15

Related Article: Smoking rates fall most significantly in the North of England

More support is required for colleagues in the devolved nations to ensure they implement their own national programmes to save more UK lives.16 However, it will also be critical to monitor and evaluate the actual roll-out in England in terms of its reporting system, turnaround times, workforce, and tailoring screening to consider local population and service needs.

Challenges with uptake

While the rate of uptake by individuals has increased, the variance in uptake of different local TLHCS at last evaluation ranged range from 20%-79%.12 Also, a significant number of individuals book but fail to attend the initial screening interview. The UK Lung Cancer Screening (UKLS) Trial revealed that two main themes emerged among high-risk groups who failed to participate – reflecting both practical (related to age, geography or low socio-economic group) and emotional barriers such as cancer fear and stigma.17

Getting the service model right is key. People can either ‘opt out’ (where they receive a letter inviting them to attend an appointment at a specific time) – or they can ‘opt in’ (they receive a letter asking them to contact their local service to make an appointment). Initial data show that the opt out approach tends to be more effective – but the current TLHC Programme data has many caveats. New TLHC projects are advised to try both options to see what works best in their area.12

Case study: The Nottingham TLHC programme has invited over 35,000 people to TLHCs since April 2021. Patients are identified by primary care, but the invitations, follow up and interpretation of investigations is undertaken entirely by the TLHC team. Many primary care centres do not have the resources to actively support a programme and using this approach has seen practices engage with the ‘hands off’ approach, leading to uptake rates with practices up to 70% in some areas.

The success of this lies in its ‘opt out’ model and a detailed understanding of the local communities and the flexibility to tailor the service to all relevant groups of people. This has included an invitation approach using both letters and text messages, a mobile CT scanner located in local communities and shopping centres, and targeted communications including local radio advertising, local pharmacy promotion and a dedicated website translated into several different languages.12

What can nurses in the community do to support screening and early detection?

Related Article: Boost your CPD with the redesigned Nursing in Practice 365 platform

Nurses in the community can play a crucial role in supporting lung cancer screening – and are an important advocate for early detection. Firstly, nurses can help to educate patients about the importance of lung cancer screening, especially for those at higher risk due to smoking. They can also raise awareness about symptoms (such as persistent cough, chest pain, or unexplained weight loss) that might warrant further investigation. Practice nurses can actively promote local lung health checks and address any fears and misconceptions – navigating the patient through the process and provide any emotional and practical support. They can also promote the service among other clinicians and primary healthcare professionals within their own organisations and teams. Lastly, but not least, they can connect patients with local smoking cessation services and encourage quitting – which is crucial to the success of any screening programme.

Dr Daryl Freeman is an associate clinical director in primary care, clinical adviser, respiratory, Norfolk & Waveney ICB and a Director of the UK Lung Cancer Coalition (UKLCC): www.uklcc.org.uk

References

- Cancer Research UK. Lung Cancer Statistics

- National Lung Cancer Audit: State of the Nations Report V2: page 5. (May 2024).

- De Angelis R, Sant M, Coleman M et al. Cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007 by country and age: results of EUROCARE-5—a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15 (1): 23–34

- De Koning et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial:. N Engl J Med2020;382:503-513

- Field et al. UK Lung Screening Trial (UKLS). Health Technol Assess 2016; 20: 1-146

- NHS University College Hospitals London. The SUMMIT Study.

- Cancer Research UK. Survival for Lung Cancer.

- Bhopal A et al. Lung cancer in never-smokers: a hidden disease. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2019;112(7):269-271

- Forrest L et al. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Lung Cancer Treatment: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Med 2013 10(2): e1001376

- UK National Screening Committee. Lung Cancer Screening Recommendation. September 2022

- New lung cancer screening roll out to detect cancer sooner. June 2023

- UK Lung Cancer Coalition. Presentations made at the UKLCC Driving Quality Improvements in UK Lung Cancer Care Conference, London, November 2023. Published February 2024

- NHS England. Cancer Programme progress update – Spring 2024. May 2024

- National Disease Registration Service. Rapid Cancer Registration Dataset.

- Welsh Parliament. Questions to the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Social Care in Wales – update on Lung Cancer Screening Pilot South Wales Central region. 3 July 2024

- Cancer Research UK. Lung cancer screening could save thousands of lives in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. 5 December 2023

- Ali N, Lifford KJ, Carter B et al. 2015. Barriers to uptake among high-risk individuals declining participation in lung cancer screening: a mixed methods analysis of the UK Lung Cancer Screening (UKLS) trial. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e008254

See how our symptom tool can help you make better sense of patient presentations

Click here to search a symptom